TOTAL MAN

An Essay in the Systematics of Human Nature

J. G. Bennett1. INTRODUCTION

We start with the assumption that the substantial problems of human fife cannot be solved piecemeal and that we cannot hope to understand our situation if we confine our investigation to those parts of it with which we happen to be directly concerned, or even to all that it is possible to know by observation and experiment. We shall, therefore, take the notion of Total Man1 to signify recognition that there is much about man that we cannot know, do not know, cannot yet know, and perhaps never will know and that must nevertheless be allowed for if we are to understand how things are with us. This being so, any enquiry into the nature of man must start with the expectation that the results can only be tentative; and so, before embarking on the enquiry, we must indicate, or rather suggest, what we understand by the term Total Man. Because of the diversity of his constitution, man is a totality rather than a whole. This can best be grasped by noting that man is concerned in and lives in many different worlds at the same time. This association with a multiplicity of worlds, each making a different contribution to the total man, makes the task of describing human nature very complicated. The difficulty of dealing with the situation is enhanced by the conflicting demands made upon us by each of the different worlds to which we belong. The difficulty is inescapable because, whether we like it or not, we have to live in them all. We cannot for long ignore the worlds that, at a given moment, happen not to suit us, or fail to arouse our interest.

There are two ways of dealing with complex, or multivariate, problems. One is to introduce arbitrary simplifications so that we can use the techniques of analysis that may be available. This is the mathematical approach. The other is to accept the complexity as an irreducible element in the situation and search for a structure or pattern that will enable us to examine it as a whole. This is the systematic approach and the one that we shall follow in this paper.2

2. MAN AND HIS WORLDS - THE HUMAN MONAD

The first step then, is to look at man, in his immense complexity. squarely in the face. This again can be done in two ways. One is to take man to pieces and enumerate as many as possible of his constituent elements. The second is to look at him in his total environment - that by reference to all the worlds to which he belongs. We then can define man in terms of all that he receives from and gives to his worlds, including the inner world of his own experience. The two procedures should lead to the same result; but the second has the advantage of allowing for the elements that we cannot observe directly.

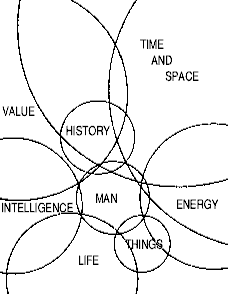

We shall not attempt an exhaustive statement of the 'human monad'3 but rather suggest how it can be arrived at. The situation be represented as the envelope of a family of curves: the latter are the various worlds and the envelope itself contains the total man, Fig.1).

Fig.1 Eight Worlds of Man

(i) The World of Energies

We can start with the concept of man as a physical system undergoing exchanges of energy.4 The World of energy transformations includes man in a special way, for his fife process is a complex system much of which escapes observation. Energies are constantly undergoing transformations throughout the universe, in the galaxies, in the stars, the planets, in all life on the earth, down to the atoms and sub-atomic particles. We are only beginning to have some notion of the complexity of the process. We men are concerned, at every moment of our existence, in the transformations of energy in progress everywhere. This is an inescapable condition of being what we are.

(ii) The World of Things

The world of energies is not the whole story. We are related to a second world that partly overlaps and partly emerges from the world of energies. That is the world of things. By the word thing, we mean what everyone else means; that is, a material object, usually solid, that we can see, touch and handle; and, to some extent, alter and use for our own purpose. The largest 'thing' with which we are in contact is the planet Earth. And our bodies are also things, and we must know ourselves under the aspect of thinghood; for a remarkably large part of our existence is occupied in dealing with things.

(iii) The World of Life

The third world overlaps that of material objects and also penetrates all our experience; it is the world of life. We belong to the world of life because we are ourselves living beings. We depend upon life for our own life. We must eat food which, whether it is animal food or vegetable foood, originates in the world of life. We have to give back to life what we take from it, that is, the substance of our living organism. The world of life is immense and only a small part is directly relevant to man. It is now generally agreed that life is probably present in some form throughout the whole universe; but hitherto almost no evidence has been discovered to support the supposition. The supposition implies that there is an almost infinite realm of life about which so far we know nothing. We know life on this earth and even that we understand very imperfectly. This third world contributes much to the constitution of man, but we occupy only a small part of it.

(iv) The World of Intelligence

Proceeding further we find, partly overlapping the world of life, a world of intelligence5 or consciousness. Intelligence, as most people would agree, is more than life. It adds a dimension to our constitution. Our thought process, our feeling reactions, our powers of attention, of choice, of understanding and in general all our psychic functions, are situated in what we call our 'inner world'. These powers and functions are not confined to man as we can verify by the fact that we recognize evidences of intelligence at all levels in the world of life. We may feel, even if we cannot verify it, that, behind life itself, there is some Great Intelligence that directs the processes of life as a whole.

Perhaps we even feel that there is a Supreme Intelligence behind the whole process of the world. Such phrases as 'God is a Mathematician' express this feeling. We can probably admit that there may be more intelligence in the world than we yet know about. This would mean there are more powers of the mind than we have yet discovered in man and also minds different in their nature and operation from those we find in man. We can take it that there is an immense world of intelligence in which we have a substantial stake; if only because intellgence is usually regarded as the characteristic mark of the animal we call homo sapiens. The human person is an intelligent being and shall therefore include "other people" in the world of intelligence.

(v) The World of Value

Distinct from the world of intelligence, there is another world, more intangible, that we shall call the world of Value.6 It is the domain of appreciation, taste; of moral, aesthetic and practical judgments. We cannot eliminate the peculiar qualities of goodness, beauty and kindness, and all the motivating influences by which our lives are directed, by reducing them to properties of life or even intelligence. Moreover, in assessing the place of values, we cannot confine ourselves to human experience, unless we are prepared to assert that values have no objective reality.

We are not concerned to assert that values are objective; the point is simply that they are different in kind from things and thoughts. The only question that concerns us here is whether values - irrespective of objective status - are exclusively human or whether they constitute a world that extends beyond man and even beyond this planet. This is not a factual question; for values, whatever they may be, are not facts. Most people who ask themselves if values are exclusively human discover an almost imperative intuition that they are given in experience and not fashioned or created by man. In this sense they are 'objective'. We can make the theoretical experiment of visiting another planet inhabited by intelligent beings. There is not a priori reason why such beings should have any sense of value; but we would be very surprised if it were otherwise. We do not mean by this that it is self-evident that the sense of value is distinct from the operations of intelligence. We may not be justified in separating them. There is no such difficulty in distinguishing the world of values from the worlds of energies, things and living beings. These are the worlds we can enter and modify by intelligence but we cannot deal with values in the same way. Value is an immediate experience of man, but its very nature is to make him aware of value as 'other' than himself. observation seems to require us to regard the world of values as an independent reality.

(vi) The World of History

The four worlds so far considered are all extensions of the 'here and now' of human experience in dimensions independent of time; or, in simpler terms, they are round about us all the time. There is another extension, into past and future, which is the world of history. History stands out from the general world process by reason of an element of special significance that enables us to distinguish events that are noteworthy, and therefore to be remembered, from those that, being unimportant, sink rapidly into the lost regions of the past.7 On this view of history, it is a world that exists in the past but influences the present. It is the world of significant traces.8 If we pause to reflect on the situation, we can recognize innumerable ways in which the world of history is one of the determinants of every individual life. It also makes a contribution different from those of any of the first five worlds. Though history is immense, its traces are concentrated in a relatively small region of human consciousness. The unconscious influences of history are far greater and more decisive than those of which we are aware. It is by no means easy to say 'where' history is located. The ontological status of the past has received singularly little attention from philosophers having regard to its immense importance for any evaluation of human destiny. There are good grounds for believing that the past exists in proportion to the intensity of the traces left by different events. It would follow that the world of history co-exists with the present and, as an extension of the present, is an integral part of our own reality. In a very real sense, we exist in the past and the past exists in us.

(vii) The World of Space and Time

Since relativity has taught us that there is no ontological partition of space and time, we must ask ourselves if there is yet another world of space-time that contributes to our constitution. At first, it would seem that the world of energies gives all that space could give. On further consideration we can see that the characteristics of space: length, direction, translation, rotation, acceleration and other field properties, are all directly relevant for understanding human nature. There is, however, far more to it than geometry and mechanics. Space is the bearer of structural form and pattern. There are ample grounds for concluding that there is a non-casual connection between patterns that determine the possible forms of events. This has been tentatively explored by Dr. Carl Jung under the designation of synchronicity.9 We know little of the properties of space and less of their influence upon our lives. Nevertheless we should recognise that there is a seventh world of space or non-causal connectedness to which we belong.

(viii) The World of Spirit

The seven worlds do not contain the whole story because they do not take account of the influences that are beyond sense and mental processes. Even subtle elements such as values are recognised in what we see, hear and touch. Values act upon our conscious experience and we should not be aware of them except as exemplified in objects or actions, in people and in behaviour. When all these are taken into account there remain other factors relevant for describing the human totality.

The circles in our diagram represent all that can be known about man and we assume that this totality is a coherent, consistent whole. Ideally, this can be represented by a set of symbols each standing for one of the elements or groups of elements that together constitute the human being. Now, Godel's theorem10 tells us that in any such system it is possible to construct statements that, though necessarily either true or false, cannot be proved or disproved within the limits of the system itself. In order to demonstrate that such statements are necessarily true false, we must construct a richer system that will provide the elements requisite for the proof.

This notion can be applied, at least qualitatively, to the human situation, if we consider such a statement as 'man is capable of comprehending the totality of any of his worlds'. This statement is meaningful but it cannot be proved or falsified. An almost equivalent statement is 'Man's perfectibility has no limit'. Obviously, this statement is charged with explosive significance. If it is true, we can deduce from it various propositions about Immortality and Deity that are commonly regarded as outside the field of philosophical enquiry. Very probably it is either necessarily true or necessarily false according to the meaning attached to the word 'man'. But, unfortunately, it cannot be proved or disproved within the limits of any knowable world.

We can then ask the question whether man participates in one or more 'unknowable' worlds. The question cannot be answered in terms of any possible 'knowledge'. But this need not prevent us from exploring the consequences of answering it in the affirmative.

We can agree to assign to this unknowable world all the irrational elements in human experience. In this we are fortified by the generally accepted view that no wholly rational statement can be made on every subject: for every statement requires at least one irrational presupposition.

Our eighth, irrational world will contain such elements as will, freedom, responsibility and the very purpose of existence itself. It will also contain elements needed for the proof or disproof of the proposition regarding the limitless perfectibility of man.

Very little reflection will suffice to convince us that, whether or not the irrational world is real objectively, it has a very real place in our understanding. It is certainly complex and it lies wholly outside the worlds of our conscious experience. We shall designate this eighth domain, the world of spirit and assume that it pervades all existence. Whatever degree of reality or unreality we may ascribe to it, the spiritual or irrational world is a factor with which we have to reckon.

3. POWERS AND FUNCTIONS

We have now indicated the meaning we wish to attach to the: term 'total man', by reference to the eight worlds of energies, things, life, intelligence, values, history, space-time and spirit. We must now enter the circle of man's own nature and see how he is able to maintain so diverse an existence. We shall use the general term 'powers' to designate all the functional mechanisms whereby man maintains his existence and responds to the various influences that act upon him. Thus there can be mechanical, physiological, psychological, conscious and supraconscious powers, for the exercise of which man is furnished with elaborate mechanisms, of which we know some from external observation, and others by introspection or self-observation. There are, no doubt, yet other powers that we cannot observe directly in either way: but infer from the conviction that man has a certain creative freedom and is therefore at least to some degree responsible for his own destiny and for his actions in the various worlds to which he belongs.

The complexity of man's nature is so remarkable as to constitute the most significant data to be accounted for in trying to understand it. The energetic, mechanical, anatomical and physiological complexity of the human organism does not end the story. The human psyche, though quantitatively less complicated, is even more diversified qualitatively in its powers of adaptation and response. We seldom take all this complexity into account in our dealings with ourselves and others. This is probably due to the selective influence of the factors that act directly upon our nervous system. We are unduly influenced by the pressures that the material world exert on us. Modern man is, probably more than his ancestors, dependent upon things, and he experiences a growing need, real or imaginary, for material objects of ever-increasing complexity. At all times, we men have been subject to the pressures exerted on us by the basic needs for energies, for food and for material objects. These tend to deflect our attention from the finer demands of our intelligence and of our nature as persons, which are usually experienced only as the desire to satisfy our emotional urges. These varied pressures occupy so much of our time and our strength, that our place in the remaining worlds is often disregarded. The influences of these other worlds pass through us with little or no attempt on our own part to discover what they might mean for us. It cannot seriously be argued that man is an animal concerned only with material objects, food and the satisfaction of organic impulses, or that the preservation of our existence in face of the dangers of wholesale self-destruction by war, famine or the exhaustion of natural resources can be an adequate occupation for our powers. A re-appraisement is therefore more than overdue.

4. THE HUMAN DYAD

At this point, our concern with total man divides into two mutually exclusive fields; one refers to the inescapable needs of life in this living animal body. This can be called the restricted concern for it is confined to the contents of the circle and does not take account of what is beyond its immediate contacts. The second is a total concern directed to the whole mystery of what is beyond our immediate reach. We cannot ignore this total concern, because it refers to influences which are constantly entering our lives and changing them in unexpected ways. We find that we have only a very limited power of living in isolation from the greater worlds which intersect our small world of individual man. Unexpectednesses are happening all the time. Sometimes they take the form of enrichment by the new wonders that come into our lives; sometimes of disasters, unexpected and unexplained. These unaccountable factors in human life may come from any of the eight worlds and beyond. Sometimes we call these factors accidents, sometimes we call them fate. We believe that we can explain and understand some of them; but even so, we remain subject both to influences whose scale is too great for us to do much about them, and also to influences that seem, by their very nature, to be irrational and unaccountable. In spite of our dislike of what we cannot understand, are all more or less drawn towards the unknown and even the irrational. This shows itself in our time in the popular features in the newspapers and radio, in the curiosity that is aroused by unexpected or unexplained occurrences, in most aesthetic and cultural activities, in religion, science and art.

Man can never be satisfied with what he has, even in the realm of material things. One might have predicted in studying the content of total man that it would be an easy problem to come to terms with the material world and decide just what is really necessary in regard to material objects. We might even have expected that man should by now have ceased to concern himself with all that is not neccessary the material world in order to live more richly in all the other worlds.

But man is so made that he can never let well alone. We are confronted with the strange property of man that the more he has the more he wants. The thirst for more than what we have prevents us from accepting the inevitable even in fields where our powers are obviously limited. A life span of so many years on this earth is allotted to man. Few men are wholly reconciled to their three score years and ten when they contemplate the vast duration of human history and the wealth of experience denied to us by the paucity of our days. Even if we are obliged to put away the thought of living for centuries, there remains the hunger for life and for more life. The same is true of the world of intelligence. We never can be satisfied with what we know or with the experiences and feelings that we are able to have. If we know, we want to know more. If we have feeling experiences and emotional satisfactions, we want more of them. Suppose we have achieved some value, something has been accomplished, either in our ordinary lives in doing a job that has satisfied us, or in that we are creative artists who have produced something that is a genuine creation; are we satisfied? No, we are compelled by some irrational urge, that leaves us no peace, to go on and on. Man as a person is never satisfied with personality. Whatever personal relationships may give: they always seem to promise more.

We thus discover a centrifugal quality inherent in man that draws him towards all the great worlds in which he has a part. This action is opposed by another which holds him to the immediate, tangible present in which he lives. If he looks outwardly to try to achieve more, he is soon made aware that in order to get that more, he will have to make some sacrifice of what he already has. The immediate is at war with the ultimate, the lesser actual with the greater potential, the centripetal tendency to hold what he has with the centrifugal tendency to seek what he has not. We can go further and say that the more strongly a man feels this two-fold demand upon him, the more fully is he a man. To be unaware of the two conflicting tendencies means either to be content with the small immediate world of every-day life or to be lost in dreams of a greater world, without having accepted the condition that dreams are realized only in actual situations. Each of these extremes denies an essential element of human existence. Reality has no use for the man who dreams only, nor for him who does not dream at all. This is but one aspect of what can be called man's total dilemma; that is, of security and adventure, which comes from the inherent dualism of man's nature that is limited in its capacity for action and unlimited in its capacity for experience. The conflict between appetite and capacity which looks like a human weakness, proves on closer examination, to be universal and inherent in the nature of existence itself. The early Greek cosmologists, inspired no doubt by contact with Babylonian dualism, invoked strife as the principle of creation. Heraclitus saw that all must be equally concerned in the anathymiosis which kindles the fire of the 'upward path' in both the world and man.13 He saw that this requires a source, the apieron. The balance of opposites expressed in the notion of strife leads only to cycles of destruction and renewal unless it is combined with some action that can give rise to transformation and progress. The non-progressive character of human thought for more than two thousand years is one of the strangest aberrations. It is little more than a century since our views of man and the world have been transformed by the acceptance of evolutionary progress as a fundamental reality. The idea of progress with its expression in the doctrine of evolution underlies most of the prevailing conceptions of human life and destiny. There is even a tendency to regard the terrestrial paradise of the future as the key to all human problems. Pie tomorrow has taken the place of pie in the sky. So complete has been our change of outlook that we can scarcely realize the extent to which it has invalidated former modes of thought. Classical Logic is non-progressive and fails to provide the categories of thought needed in the new age. We do not find it strange today to suppose that the whole universe is moved by an urge towards the attainment of some distant incomprehensible goal. Such an idea would have been repugnant to the static thinking of earlier centuries; but, once the notion of universal evolution is accepted, it is almost inescapable. We can scarcely picture progress present in the parts and absent in the whole: it would be a strange inversion of Tennyson's 'waxing tree and waning leaf'.

This section is entitled the 'Human Dyad'. It is customary to apply this term to the sexes and regard man-woman as the basic dyad. The sexual nature of man extends far beyond the dyad; but it is, nevertheless, useful to see how the polarity of male and female matures does correspond to the dyad we have been discussing. It is generally agreed that the male characteristic is centrifugal tending towards creative activity directed away from the present. The female characteristic is centripetal tending towards conservative activity directed toward the present. Hence men tend to be visionary and women realistic. Hence also the male component of the human dyad is associated with the unlimited urge to expand and the female component with the limited urge to consolidate. It must, however, be emphasised that this sharp partition of tendencies applies only to the dyad. Men and women are also connected in progressive relationships in which quite different factors are operative.

The characteristic attribute of the dyad is complementarity. The centripetal and centrifugal trends are not in any real opposition, but entirely necessary each to the other. Man and woman are not mutually destructive, but complementary. The urge to have and to hold is not a denial of the urge to go out and search for what is new and different. The two complement and fulfil one another. Complementarity is totally different from mutual cancellation. The strength of the dyad lies in the preservation of the contradictory character of its terms; but its weakness is that it discloses no principle of self-transcendence. It does not show the way to real progress.

Entropy and Syntropy

Contrary to a common, but erroneous, interpretation of the Marxist doctrine, conflict does not ensure progress. The dyad does no more than make it necessary. We must pass on to a higher system if we are to see how progress is possible. This transition is now taking place in human thought and it is the most important symptom of this age of progress.

The 'progressive revolution' has barely started. Scientists and philosophers still cling to non-progressive concepts such as atomism, mechanism, causality and logical consistency. Nevertheless, the breach has been made and eventually a new dynamism will replace the static thinking that is our legacy from the Greeks.

An indication of the change is to be observed in the sciences of life. In the nineteenth century, and indeed until recently, biologists held to the mechanistic interpretation of life. This was partly a relic of the Cartesian view that animals are machines and partly the result of the positivistic view which denied the reality of 'purpose'. Even mechanistic biologists of the present day agree in interpreting the phenomena of life in terms of goal-seeking and directiveness. They do not readily admit that these can be understood only if there is a real meaning in purpose.

This applies not only to the higher animals but even to the simplest of living things. The very idea of progress must incline us to interpret animal, and even vegetable, behaviour in terms of an urge towards a goal. It goes without saying that we men have this urge and are constantly under its influence. On the whole, it is blind and so we tend to misunderstand and misinterpret it. It usually degenerates into the thirst for more, without seeking to answer the question more of what? If we do not understand this thirst as a need for total progress we shall be likely to interpret it in terms the acquisition of more material objects. Or else, we shall respond to it in personal terms, which can be even more dangerous, for it engenders the thirst for power over people, for power to control other men's lives. This can produce aberrations that are manifestly destructive, the strength of which comes from the fact that they are aberrations from a fundamental truth, which is, that progress is universal and that all that exists must go forward towards a goal. This truth is not yet understood even by those who invoke it.

About a hundred years ago, the doctrine that universal degradation is inevitable was, for a short time, accepted by scientists. It was made famous by Lord Kelvin's British Association address of 1865 predicting the heat death of the sun. If taken alone, without reference to the counter doctrine of progress, the second Law of Thermodynamics would deprive life and indeed existence itself of all meaning. We should be left with with no way to account for the presence of consciousness and intelligence or indeed of any world at all. If from the start, everything been running down, there is no reason why anything should have built up, and yet we have direct evidence from the earth itself that the evolutionary process has been in operation for at least a thousand million years.

Scientific thinking now inclines to the remarkable notion that, throughout existence, run two complementary actions, one that builds up and another that breaks down forms and structures. This dualism of cosmic processes was first formulated by Professor Luigi Fantappie13 of the Higher Academy of Sciences in Rome as the doctrine of the balance of entropic and syntropic actions. One tendency is for things to become weaker, softer and less interesting. This is the more 'probable' trend but it is no more real than the opposing tendency to build up from weak to strong, from simple to more complex and therefore less probable, and also more interesting, forms and structures. This dualism is almost inescapable if we wish to account for the world as it presents itself to our observation and experimentation.

The reciprocal significance of the two opposing principles of degradation and integration escaped attention for more than a century, chiefly because the first was found and used in physical science and the second made its appearance in biology. We associate the first with Carnot's Reflextions sur la puissance motrice du feu (1824) and the second with Lamarck's Philosophie Zoologique (1809) and Darwin's Origin of Species (1859).

It is only within the last decades, that evolution and involution, syntropy and entropy, have been seen as correlative processes in all departments of nature, including man himself. Even today, relatively people have yet grasped that the syntropic or up-grading tendency whereby quality is enhanced in nature, is as universal as the entropic rocess whereby there is diminution or degradation of quality. It is very probable that the failure to see the complementarity of the two terms in the dyad, accounts for the failure to appreciate the universal character of the syntropic urge that is manifested in man.

Since Boltzmann14 showed that entropy could be connected with the statistical probability of a state involving very large numbers it has been customary to look upon the entropic process as a movement towards large scale disorder. This would suggest that the syntropic trend is a reversal towards a primitive small-scale order, but the very notion of order is ambiguous. Bohm has made the pregnant distinction between non-order and disorder.15 He suggests that disorder is meaningless unless the nature of order is first understood. From the standpoint of systematics, non-order corresponds to the monad, for it is a condition in which the totality is viewed without reference to order. The dyad introduces the distinction between order and disorder not as two permanent states, but as two tendencies both always present. It is in accordance with the trend of modern cosmological thought to treat processes as having a higher status than entities. We are less and less inclined to suppose that we can know what anything is, whereas we find that we can know more and more about what things do. Relativistic and approximative notions were formerly regarded as inferior to the precise and absolute conceptions that seemed to apply in the realm of being. We have moved far away from such modes of thought, and today accept not only relativity, but even contradiction and absurdity, as normal constituents of the real world. Thus, it seems absurd to say that the connection between two processes is 'more real' than the processes themselves and yet this is undoubtedly true of the entropic and syntropic actions. Their significance cannot be grasped if either is studied out of connection with the other which is just what men have done since Zarathustra and the Buddha made dualism popular two thousand six hundred years ago.

The modem notion of the entropy-syntropy dyad differs from that implicit in the ancient cosmologies, from India to Egypt, from Chaldea and Greece, which postulated independent states of activity and repose. The endless alternation of building-up and breaking-down processes leads to a cyclic interpretation of the natural order that does not agree with the facts of observation. Cyclic phenomena are universal but not all phenomena are cyclic. We now see the secular character of the world process due to the presence of entropic and syntropic trends. The contradiction, which would have been repugnant to earlier ways of thinking, is now made acceptable by the success of Bohr's complementarity in physics and its adoption as a principle of explanation in current philosophical thought.

Applying these ideas to man, we find an authentic dyad corresponding to his twofold nature as male-female, as finite-infinite, as doomed to death and destined for immortality. The irreconcilable contradiction of death and life cannot be eradicated and in its acceptance alone can man find the way to go beyond it, that is, the key to authentic progress.

The entropic process in man consists in the replacement of the integral pattern of his innate potentialities by an increasingly contingent series of actualizations. The syntropic process in man is not a return to the primitive pattern; but the emergence of a new pattern which is made possible by the urge towards unity and coherence that runs through all actual process. We can regard man as running down from a primitive unitary state of minimum entropy and at the same time as building up from a primitive state of chaos, ie. maximum entropy. The original states of unity and chaos are fictions, because they can never be verified. The observable and verifiable reality is the presence of the two contradictory tendencies present in man from the moment of conception. In one sense, man is conceived as wholly potential, that is, in a state of minimum entropy. Looked upon in this light, his potentialities are constantly diminishing until he reaches death, ie. state of maximum entropy. This is how we can interpret Claude Bernard's aphorism: 'Living is dying'.

Nevertheless, it can also be said that man is conceived in a state of non-individuation in which there is almost complete absence of order, ie. a state of maximum entropy. From this starting point, there is an urge towards individuation that accompanies him throughout life. We may take individuation as syntropic and contrary to the process of dying. The urge towards individuality is realized in man's search for truth. It does not cancel the entropic process, but combines with it to produce the curious dualism of man's nature. Within this dualism man discovers a freedom of choice between death and life which proves to be the condition of his participation in the syntropic process. This suggests a thermo-dynamic definition of Original Sin as being the act whereby man has identified himself with the entropic process. The effect of this identification is to externalize the syntropic process so that its field becomes, not man himself, but his various worlds. Thus man is drawn to satisfy his syntropic urge by way of successful action. The condition for such action can be called in Biblical terms 'knowledge of good and evil'. It is worth mentioning that, in modern Greek, the word 'entropy' means shame or disgrace, and it was first adopted in thermodynamics to draw attention to the waste of energy inherent in the engine cycle.

The dual nature of existence has from time immemorial been represented by the tree symbol, united in its trunk and divided in its branches. It is found in mythological systems as the Nordic ash tree, Yggdrasil, and the Zoroastrian Soama tree, with its roots in Heaven and branches reaching down to earth. The growth of the tree depends upon energy exchanges that are entropic and it ends in exhaustion and death. The photo-synthetic process in the leaves is syntropic and, with return of the sap, renews the life of the tree. The point of the tree symbol is that life and death are inextricable: living is dying and dying living. Man the finite cannot know himself except in the light of his own infinity. The progressive revolution is leading us to look beyond the dyad to a different kind of transformation.

5. THE TRIAD OF HUMAN TRANSFORMATION16

The nature of the dyad is such that it cannot be eliminated except by returning to a state of non-order in which both dynamism and meaning have been lost. If, therefore, progress is a constituent of reality, we must be able to go beyond the dyad, that is, beyond death and life, not by removing its contradictions, but by transcending them.

Systematics passes from the dyad to the triad by tranforming contradiction into opposition, thus making reconciliation possible. Life and death as characteristics are in contradiction. Living and dying can, however, be looked upon as the dynamic and static manifestations of an underlying condition in which the will to live and the resistance to life stand in an opposition that can be harmonized in a dynamic relatedness. Between opposites, a relationship can be established cannot be found in contradictories.

These considerations can be applied to the human situation, if we observe how the blind urge to grasp life and to add more and more to its content, is opposed by the practical limitations of the human situation where man is wholly dependent upon his environment and yet seeks to dominate it. The conflict is resolved when the affirmation can be directed in such a way as to produce an enrichment that is shared by man and his environment. Only in this way can progress be maintained without destroying its own foundation. Understanding of this point turns upon the perception that the urge to achieve progress is totally distinct from the ability to direct it. In consequence of disregarding this we men constantly make mistakes, setting ourselves wrong goals and entertaining purposes that lead nowhere. We must learn to distinguish between the libido that drives us to action and the longing to understand what it is we have to do. This longing is fundamentally the need to understand the meaning of life. Sometimes it takes the form of an awareness of our helplessness in front of specific situations where we have the urge to act, but cannot see what action is appropriate. Man's ignorance and helplessness in front of the great problems of life is reflected in the minor situations of our social and private lives and even before the petty dilemmas that we meet from day to day. Experience shows that awareness of ignorance engenders the capacity for learning. This is the means by which the human situation passes from the dyad of living and dying to the triad of transformation which in turn holds the possibility of progress. The terms of the triad are:

First, the affirmation, or the will to be, that engenders the urge to betterment of every kind, second, the receptivity that characterizes the human organism and psyche and endows man with the capacity for experience and response, and, third, the spontaneity that introduces the element of freedom and also of contingence in all human relationships.

The three terms refer to the nature of the impulses that draw man into all kinds of situations. The first, or affirmative, impulse starts as the thirst for experience that we see in young children. Even in mature life it is seldom conscious or intentional. Only the fully developed or transformed man can truly affirm himself. The receptive impulse can be regarded as the passive or instrumental element in human nature. The instruments are both somatic and psychic - or as Feldenkrais18 has emphasised - somatic and psychic combined in one. The somatic nature with the attendant psychic functions has its powers extended outwardly by tools and machines to provide the means of action whereby will to act can find satisfaction. It is also extended inwardly by the powers associated with organic sensitivity excellently discussed by Dr. Maurice Vernet19 in an earlier paper from this Journal.

The three terms set up a system of relationships that can be repesented in terms of the six fundamental triads discussed by the author in Dramatic Universe.16 Expressed in terms of human experience, the six triads determine the kinds of transformation possible for man. As remarked above, that progress which the dyad shows to be necessary is seen in the triad as possible, or more accurately, as permissible transformations. In man fully developed and harmonized, the six laws are all exemplified. If any of them operates incompletely or imperfectly, the possibility of progress is impaired.

At this stage of the enquiry, we can make a provisional definition of human progress as: "Transformation tending towards freedom, better adaptation and more effectual action in all possible modes of relatedness". The definition implies more than mere development, since it requires harmony and mutual adaptation of instruments and powers which differ in their nature and function.

The three terms of the triad - affirmation, receptivity and spontaneity - can be related to three modes of experience: Feeling is awareness of affirmation. Sensation is awareness of receptivity. Thought is awareness of spontaneity. It will be understood that these are the ideal, or perhaps the 'normal' characteristics of the functions. Man's are only too often tinged with negativity and 'positive emotions' that are pure affirmation are rarely experienced. Sensations are usually merely passive and not the awareness of oneself as a vessel into which life is constantly pouring its riches. Thought is more often automatic association of mental or verbal images and seldom achieves the creative spontaneity which links what is and what must be. If we take the ideal qualities of feeling, sensation and thought, we find in them all the powers required for human progress.

The three in all six combinations represent the ideal situation which permits maximum rate of progress; but man is subject to a variety of disturbing influences both internal and external that seldom allow the three powers either to operate normally or to enter into their normal relationships. Thus, in some men passive sensation dominates and the urge to progress loses momentum. In others, feeling loses its affirmative character and turns into reaction to changing external influences. Then instead of producing a steady urge towards progress, it results in erratic changes of direction and loss of purpose. The misuse of the power of thought is the most prevalent of human disabilities. Thought loses its spontaneity and is usually dominated by sensation and feeling, and cannot harmonize affirmative and receptive functions and instruments. One of the principal obstacles to right thought is the unavoidable use of language that derives its forms from sensation. This prevents thought from making a direct contact with subtle objects that are not sensible. Thus, we have the distressing situation that thought, which should serve as a factor of reconciliation, becomes the principal cause of misunderstanding and disagreement. Spontaneity degenerates into randomness and thought operates merely as an automatic mechanism kept on its object by a kind of emotive feed-back.

In spite of the generally degenerate working of the human powers, we can from time to time observe striking cases of right working when the creative nature of man stands out brilliantly from the drab background of automaticity. The study of man's relationships in terms of the three qualities of affirmation, receptivity, and spontaneity, together with the corresponding powers or functions of feeling, sensation and thought provides us with a picture of human normality that is of the utmost value as an instrument of criticism and reform. This applies especially in the field of education.

6. THE TYPES OF HUMAN RELATEDNESS

The normal relationships of a man whose powers are rightly used and directed, can be seen from a summary of the types of relatedness corresponding to the six triads. The references are to Dramatic Universe Vol. II, chapters 27-31.

(i) Man as human person

Behaviour should be the expression of feelings harmoniously related to the changing environmental conditions. The human person is the pattern of his feeling experiences; but these cannot manifast rightly unless they are linked to sensation and directed by the power of thought. The triad is that of Identity: 2-3-1. When fully established, this triad nsforms man into a stable, recognisable entity able to manifest appropriately in all situations.

(ii) Man as social animal

Adaptation to the environment requires acceptance of relatedness so that the urge to self-realization should be harmonized in outward behaviour. The triad is here that of Interaction: 1-3-2. When fully established the triad of interaction confers flexibility combined with purpose and decision. The instruments are at the command of the affirmative power of the will.

(iii) Man as regulator or law-giver

In this third relationship man is the "Lord of Nature". With the insight gained through the power of thought, his urge to self-assertion expresses itself as a regulative action in the external world. This is the triad of Order: 3-1-2. The characteristic feature of this triad is stability of insight and understanding that enables man to rule himself and his subordinate worlds.

(iv) Man as free agent

The harmonizing insight of the power of thought keeps the organic and psychic instruments free from external disturbance and enables the spontaneity to be transmitted from thought to feeling and so to initiate free actions. The triad of Freedom: 3-2-1 is characterized by spontaneity. The instruments are protected from external disturbance by the spontaneity of man's inner vision. He can then be free.

(v) Man as instrument of creativity

In this case, the feelings are in harmony with the forces of nature working in the body, and thought acquires its true character of pure creativity. This is the triad of Expansion: 1-2-3. By this, man serves as a channel for the transmission of influences that arise in his feelings through contact with the greater worlds to which he belongs.

(vi) Man as evolving being

The instruments at the disposal of the urge to progress, produce an action whereby the power of thought is individuated and the man himself is transformed. This corresponds to the triad of Concentration: 2-1-3, which is the triadic counterpart of the syntropic tendency in the dyad. The difference between syntropy and concentration in man consists in the role of the human will. The syntropic influence establishes the need for progress - it draws man on. The triad of concentration is established by an act of will, whereby the powers are dedicated to the achievement of progress.

The six triads taken together determine the sum of all relationships possible for man. The first two are 'static' for they operate without changing man himself. Those that begin with the third impulse are 'open' for they allow both progress and retrogression. The last two are the triads of change. They are 'dynamic', but their direction depends upon the open triads. Order and Freedom are the basic conditions for the arising of progressive relationships between man and himself, and between man himself and all the worlds in which he has a part.

7. ACTIVITY AND TRANSFORMATION

Relatedness can be studied without reference to any specific relata. In the scheme sketched in the last section, we have the conditions of activity and progress; but not yet the objects of thought and action required to make them concrete. The transition from relatedness to activity is a progressive step forward: it takes us into the realm of activity as a constituent of the total reality.

If we are to interpret human life as activity, we shall need categories different from those which express relatedness. These categories are furnished by the tetrad, which is the simplest system that allows for the construction of ordered manifolds and hence of activity involving exchanges of energy and the various processes of realization.

We shall use the term activity to designate a complex process, that includes transformation and blending, whereby situations mature under the conditions of time and place. In its simplest expression, activity is seen in the unconstrained motions of bodies in a field of force. Even in such a simple situation four independent terms must be specified. We have (i) the bodies (ii) their motions (iii) a reference framework and (iv) the laws of motion characterizing the field. These four terms can be generalised so as to apply to all kinds of activity including non-temporal connectedness or structure. We shall confine our attention in this paper to human activity.

All activity, even random unconstrained motion, can be referred to some unifying principle - such as the Law of Least Action. Generally the principle is complex but it can be described systematically as the pattern to which the activity conforms. In a 'closed' system, the pattern uniquely determines the action; but in all concrete situations, extraneous factors arising outside the system must be taken into account. This makes it, in general, impossible to prescribe the pattern exactly and we may not even know the form it takes. This need not be an obstacle to understanding the situation for it is sufficient that we should be confident that there is something to be understood. This requires that the nature of the 'something' can, in principle at least, be inferred from the observable facts of the situation. The prime observables are sense data which, passing through the stages of sensing, perceiving, knowing, interpreting and relating, finally lead us to understand what is going on. Thus, the activity that we seek to understand has its own pattern or structure, its own processes; and, in the case of human activity, it has also elements of knowing and doing. It is not easy to find descriptive names to distinguish the four terms; chiefly because we are not accustomed to, treat human activity as an ordered whole, in which what happens, what is perceived and what is fed back into the human agents, are jointly regarded as constituting the activity itself. On the contrary, we have ingrained habits of dividing the subjective and the objective elements in experience and of disregarding the unifying or structural term, so that we lose the unity of activity that is the only concrete reality.

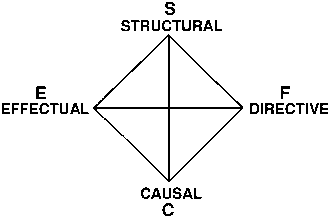

Various attempts have been made to establish a terminology that will express this unity. In the present paper, we have adopted names for the four terms that apply not only to human activity, but to complex transformations - whenever and wherever an underlying pattern can be postulated. The four terms are Structural Process, Causal Process, Effectual Process and Directive Process. The meaning of these can best be grasped by applying them to concrete situations; but for lack of space we shall give brief descriptions of them in general terms.

1. Structural Process. Symbol S.

In human activity, we are aware of a sense of obligation or purpose that is never wholly conscious and is usually outside the field of consciousness, but influences all that we do. We postulate a source of this influence that we call the pattern or structure of the human life or lives participating in the activity. Even if we are not prepared to accept the notion of both individual and collective destinies, we cannot account for the coherence and pattern in the events of human life without postulating some underlying structure.

2. Causal Process. Symbol C.

Here there is nothing mysterious that must be taken on trust. We find in sense data regularities that we interpret in terms of cause and effect. This notion, as Henri Poincare showed, is probably derived from the combination of visual and tactile sensations. All activity in which we participate is influenced by the stream of sensations that enter our consciousness from the 'external' source.

3. Directive Process. Symbol F.

The external world influences the activity indirectly through the agency of the human participants. We have in any given situation, a variety of contacts with the seven or eight worlds that determine the human monad. These contacts are transformed into accumulated experience in the form of knowledge of the world. The normal function of this knowledge is to enable the activity to be so directed as to produce intended results. For this reason the term is called the directive process. Its normal vehicle is thought. It can be looked upon as the masculine element in the human activity. The true character of masculinity consists in being a channel of transmission. This is evident in sexual reproduction, tion, but it can be recognized as the male contribution to every kind of activity. The fertilizing impulse is both directional and transmissive. In human activity this element relates the immediate present to the various worlds present, past and future.

4. Effectual Process. Symbol E.

The last element in activity consists in the use of the instruments of action. This is the practical or effectual term of the tetrad that closes the circuit and converts the activity into an actual situation. This element can be compared to the prime mover in a mechanical system. In man, it is associated with the emotive impulse or the power of feeling. This may appear strange until we reflect upon the role of the feelings in translating ideas into action. Unless there is a response in the feelings and the response usually depends upon preformed emotive habits - ideas that arise spontaneously in the mind remain inoperative. At the very least, we must be 'interested' in an idea before it makes us act.

The effectual term can also be regarded as the feminine or 'mother' term. It 'keeps house' for the activity in the process of realizing structure in experience and of unifying experience in structure.

Man's nature is such that he can reproduce all the four terms within his own activity. In this sense, he can be called a 'cosmos' or well-ordered system. This makes it possible for man to prosper as an individual and partly answers the question of perfectibility which cannot be decided in the dyad. (cf. p.287.) Systems that lack one of the four elements are dependent upon their environment and their progress or recession depends upon what is happening in some larger whole of which they form a part. It must be evident that this is more or less true for man also, especially if his own powers are imperfectly developed or he fails to direct them wisely.

The tetrad just outlined can be related to the Jungian scheme of Intuition, Sensation, Thought and Feeling; but these four terms express rather the instruments of activity than forms of the activity itself. Moreover, it must be remembered that we are, at this stage, concerned only with what man does and not yet with the significance or potentiality latent in his activity. We can, however, ask, and try to answer, the question: what makes for successful activity?

The Structure of Human Activity

The tetrad can be represented by a square with its diagonals in wh the four corners stand for the four terms and the six cross-connections indicate the types of action which must be combined to produce a complete and harmonious process.

Fig. 2. The Tetrad in Man

E-F Conscious Experience. It is easy to verify that our conscious experience is mainly occupied with awareness of the directive and effectual processes. We do not, usually, pay attention to our immediate sensations to which we react by subconscious reflexes. The 'stream of thought' is commonly regarded as a state of self-awareness, chiefly because it is the seat of directive and effectual impulses. In practice, there is seldom more than semi-awareness. As can readily be verified, we are seldom aware of the combined action of thought and feeling. This leads to a dissociation of direction and action with marked loss of effectiveness. When the connection E-F is attenuated to a point where the two sources of the process lose touch with one another; we fall into a state of automatic external behaviour dissociated from the inward state of day-dreaming or reverie. The connection is strengthened by all purposive and sustained activity. At its best, it is true self-consciousness.

S-C Motivation. Through the causal process, man is driven like a machine by the stream of sense impressions coming from without. Through the structural process, he is drawn to realize the pattern inherent in his own nature. Between the two extremes we can discover a range of motivating impulses that give shape to all human activity. The motivations originate almost entirely outside conscious experience. The somewhat startling conclusion that man seldom exercises any conscious control over his own motives, is confirmed by the findings of analytical psychology. It seems legitimate to regard the structural process as supraconscious and the causal process as subconscious.

S-E Conscience. The capacity for effectual action should be harnessed to a sense of purpose derived from the structural term. This can take several forms. The man in whom the connection is strong is guided by a sense of purpose and the need to seek fulfilment in an ideal recognized as unattainable. The connection S-E is the seat of conscience - moral, practical and artistic, of taste, judgment and a feeling for harmony and fitness.

S-F Faith. This connection is the source of confidence in the ultimate rightness of the universe. According to a man's formation and traditions, it may be expressed as belief in divine love and justice, or as confidence that the order of nature is not deceptive. It is the main-spring of man's search for truth, for without faith of some kind there can be no starting point.

E-C Practicality. The connection between the effectual and causal elements makes the successful doer. It ensures skill in the use of the human instruments in the given environmental conditions. Those in whom this connection is strong, have a realistic and practical attitude towards life. Its development consists in the acquisition of skills.

F-C Curiosity. The desire to know the world comes from this connection. It enables successful planning of activity; but may also result in a tendency to think rather than to act. The Jungian distinction of intraversion and extraversion applies to over-emphasis of the F-C and E-C connections respectively. Curiosity in the best sense seeks to unite man and his world.

The tetradic scheme can be used for the assessment of individual. abilities and also for analysing complex activities to see where greater effectiveness can be secured. It has been found that individual charts based upon an evaluation of:

- the relative dominance of each of the four elements S, C, F and E,

- the motivational spectrum S-C,

- the balance of directive and effectual powers, F-E,

- the strength of the four lateral connections, S-E, S-F, E-C and F-C,

provides a reliable assessment of the likelihood that a given individual will be successful in various types of activity. This techniques has been applied to the known characteristics of some of the great scientists of past and present centuries and has proved useful in reaching a better understanding of their creative work.

Significance as Applied to Man

We are now ready to examine the question whether or not human life has a meaning. Before we can start our enquiry, we must agree at 'meaning' means in this context. The notion of significance is bound up with other notions such as potentiality, spontaneity and freedom. If all were equally 'actual' there would be no way of standing apart from it to ask questions about meaning. If there were no spontaneity, there would be no room for freedom and if there were no freedom, there would be no significance. We shall look for significance in the potentiality of the individual for transformation and also in his place in a whole or totality.

We can best bring out the meaning that the word significance has for our enquiry by embodying it in three sentences that may appear self-evident.

- Significance requires spontaneity and some degree of freedom.

- Significance of the part implies significance of the whole.

- Significance of any entity requires some degree of independence.

This suggests three questions about significance that we must answer.

- Where and in what does significance reside?

- Can there be significance of any part for itself, ie. distinct from that which it acquires from its whole?

- Can the part be significant for the whole, ie. can there be a transfer of significance?

As applied to man, these three questions require us to consider firstly, what man himself is; secondly, what is the self within which he can have a significance of his own; and, thirdly, what is the whole or totality within which he can be significant?

The two latter questions also themselves suggest the subsidiary, but obviously important, point that there must be limits to any kind of significance which we can hope to understand. There can be no meaning for us in putting the question as whether a small 'part', such as a grain of sand, can be significant for a very great 'whole', such as a galaxy. There must, in the life of man himself, be events too trivial to count in the assessment of significance, and also an upper limit to the total significance which he could claim or aspire to.

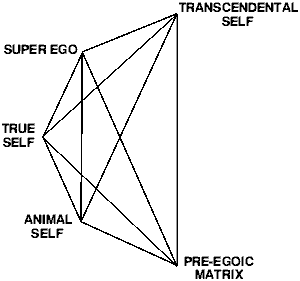

From these considerations, we arrive at a five-fold structure of significance represented by the diagram in Fig.3.

Fig. 3. The Pentad of Significance of Man

The limits of inner significance range from the instinctive needs associated with our animal existence to the aim of fulfilment in the hypothetical super-ego.

In the diagram these are shown below and above the central point, designated as the True Self or "I". This tends to give the impression that the animal self is inferior and undesirable, and that the super-ego the source of all that has positive significance in human life. Such an interpretation would be totally misleading, if only because man would lose his identity if he were divorced from the animal self, through which he is located in the worlds of energy, thinghood and life. It might be better to represent the relationship in the form of three circles, the outer circle being that of the animal self, and the inner circle the super-ego. This would bring out the connection between significance and withinness, and relate our scheme to that of Teilhard de Chardin in his, Phenomenon of Man.

The true self or "I" is the seat of man's self-conscious will and should therefore be the centre from which his entire life is governed. On account of the decisive role played by the true self, there is a tendency to regard it as the highest constitutent of man's nature. This is to attach undue significance to consciousness and it runs counter to the best attested observations of analytical psychology. The early view that divided man into conscious and sub-conscious parts has been replaced by the trialism of conscious, sub-conscious and supra-conscious already referred to. There is a tendency to misinterpret the term 'supra-conscious' to mean a heightened or more intense consciousness, such as that which is experienced in narcotic or mystical states. The unfortunate term 'Cosmic Consciousness'20 has led to undue importance being attached to such states, which prove in practice to play only a minor part in the complete and harmonious development of man. For reasons which cannot be elaborated here, we should take the super-ego as standing beyond the reach of conscious experience. It should be associated with the Creative Energy, for an account of which reference should be made to the second volume of Dramatic Universe.21 On this interpretation, the significance of human life is to be found in the development of the True Self of man as a bridge between the universal but diverse forms of awareness associated with animal life and the creative power that is beyond consciousness and located in the super-ego or individuality.22 Until this link is established, individual man has no significance that is both his own and also total.

The significance of man cannot be understood by reference to a single self in isolation from others. We have therefore to take the other two points of the diagram into consideration. The term pre-egoic matrix introduced here to designate the blind urge towards progress and has been referred to in earlier sections, but is now made specific as a property that characterizes a particular level of existence at the threshold of life. If we regard the evolutionary process as a trend towards withinness suggested by Teilhard de Chardin,19 then we should expect to find a point at which withinness begins to be observable in separate entities. This can be compared to a change of state in material systems, such as the melting point of ice. We connect it with the generative power that distinguishes living from non-living matter, and therefore it has been called the 'germinal essence'.23 In every germ, there is potential for individuation; and, in the case of man, this comes into operation at the moment of conception. In an important sense, therefore, the lower limit of human significance consists in the fact that man develops from a germ. In another sense, we can say that man participates in the total syntropic striving of life. In its most primitive form, this basic syntropic activity can be called the pre-egoic matrix.

Turning to the other extreme of human significance, we can postulate an Ultimate Purpose that is commensurate with man's relatively humble size and place in the universe. It would be ludicrous, in the present state of our knowledge of the world, to suppose that individual man, or even the entire human race, can be significant for the whole universe or even for our own galaxy with its hundred thousand million suns. There must, therefore, be an upper limit to the utmost conceivable significance, and this can be inferred from the fact that the significance man is linked to his individuality. For this reason the upper point is designated the Transcendental Self, which seems preferable to less personal terms such as Universal or Cosmic Purpose, or more committed terms such as God or Christ.

If we examine the five-pointed symbol Fig.3, we see that there are ten connections joining the five points to each of the four others. Each of these connections can be interpreted as a significant link in the interpretation of human destiny. We shall finish this study by giving a brief indication of the way they can be applied to the problem.

Animal Self - Super Ego. The vertical line represents the whole nature of man with all his instruments for perception, reflection, action, sub-conscious, conscious and super-conscious. It is the anatomy of the complete man.

Super Ego - True Self. This gives the inner orientation of human purposes. From this connection arises the sense of responsiblity toward oneself. It is the source of the moral conscience.

True Self - Animal Self. Man's dependence upon and responsibility for his animal existence are represented here. This is the direction of the will. If this line fails or weakens, control passes into the animal self and man loses touch with his own true nature.

True Self - Pre-egoic Matrix. This connection discloses the secret of man's inner transformation. He draws into himself and concentrates and brings to consciousness the urge to life by which he is pervaded and surrounded. Unless this urge is consciously directed and reinforced by the individual will, it produces only disruptive tendencies which finally destroy the self. The line can be taken as having two directions, one indicating the pull upon man of the blind striving of the world, and the other, the power that resides in man himself to master this striving and convert it into the strength of his own being.

True Self - Transcendental Self. In this line we find the significance and purpose of man's life in an objective sense. It completes, with the connection of the true self and super-ego, the triad of man's ultimate destiny. The strength which man acquires through transformation of the pre-egoic matrix would be wasted if it could not be placed in the service of an ultimate purpose that transcends the limitations of man's personal existence.

Super-ego - Transcendental Self. Here we have a connection that cannot be brought within the focus of consciousness and its nature must therefore be a matter of conjecture. According to some views, the super-ego is, by its nature, that is without any transformation, in harmony with the transcendental self. According to other views, there is a supra-conscious process whereby individual creativity faces the issue of harmonizing self-determination and self-effacement.

Animal Self - Pre-egoic Matrix. This comprises all the natural processes of life whereby the individual organism maintains itself at the expense of its environment, but also returns to its environment the materials that it has borrowed. This applies not only in bio-chemical terms, but also in relation to the psychic energy associated with the pre-egoic striving.

The Perfected Human Individual

The existential view that man's significance resides in himself alone and that he and no one else can bring significance into his external world is most dangerous half-truth - or more exactly, one-fifth of a truth, for it takes account only of the lower connections of the self. The destiny of man, on any balanced view, must take account of his obligations as well as his rights. The systematic scheme of the pentad shows him as under three kinds of obligation. One is to himself, another to the ideal of human perfection as exemplified in the 'super-ego' and the third is to an objective purpose that is beyond humanity. If any of these three are neglected, man cannot attain to the complete significance which is his destiny. Conversely, man draws upon three sources: his pre-egoic environment, his own animal nature and the potentialities latent in his true self. These six taken together bring us from the pentad to the hexad and show what is to be a Perfected Human Individual. The detailed examination of the hexad would take us beyond the scope of the present enquiry for it requires a study of cosmic origins and purposes.

Conclusion

The purpose of the present paper has been to show that it is possible to represent a wide range of notions about man, his nature and his destiny, in a consistent way by applying the method of systematics. The identification of the terms in the various systems and the interpretation of the cross connections are tentative and have been given for the purposes of illustration only. Space would not allow the requisite detailed examination to show why a particular interpretation has been adopted, therefore no claim is made for objective validity of any part of the scheme. It will, nevertheless, be found that the presentation of human nature in systematic form, allows us to keep before our minds the total picture in a way that would be difficult, almost impossible, by the use of discursive description or functional analysis. Those interested in a fuller presentation of the notions briefly sketched in this paper are referred to the author's forthcoming book A Spiritual Psychology.24

REFERENCES

- The title of this paper is taken from an address given by the author at the inaugural meeting of the Manchester Branch of the Institute on January 22nd, 1964. The paper is based on the subject matter of the address.

- C.f. Article on General Systematics in Vol.1. No.1 of this Journal.

- The Monad is the one-term system with the attribute of universality. The human monad is the universe of man.

- Energies include all states of matter capable of doing work: physical, vital or conscious. C.f. "Dramatic Universe" Vol.II. Chapter 32.

- Intelligence includes all modes of cognition. All intelligent beings are the "world of intelligence". It does not include the objects of knowledge nor non-cognitive experience such as willing and judging.

- The dyad Fact-Value is discussed in Dramatic Universe Vol.II. Chapter 25.

- C.f. N. Berdyaev, The Meaning of History p.23 "A purely objective history would be incomprehensible. We seek an inner profound and mysterious tie with the historical object".

- The notion of 'significant trace' is due to Professor David Bohm.

- C. Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections, p.356 "There are psychic parallelisms, which cannot be related to one another causally, but which must be connected by another principle ... hence the term synchronicity".

- K. Godel, Uber formal unentscheidbare, Saitze. 1931.

- The dyad is the two-term system with the attribute of complementarity.

- C. Bailey The Greek Atomists and Epicurus 1928 p.20. The upward and the downward path according to Heraclitus are "one and the same". This may express an intuition of the complementarity of the two processes.

- L. Fantappie Principi di Una Teoria Unitaria del Mondo Fisico e Biologico. Rome 1944. pp.42-56.

- L. Boltzmann, Vorlesungen 1896, identified entropy with the logarithm of a probability, rather than the probability itself, because entropy is an additive quantity.

- D. Bohm, Casuality and Chance in Modern Physics. 1962.

- The triad or three-term system has the attribute of relatedness. It can be shown that all relationships can be expressed in terms of three independent factors having the properties of affirmation, receptivity and reconciliation C.f. Dramatic Universe, Vol.II. Chapter 26.

- Henri Poincare, La Valeur de la Science Paris. 1942. This important posthumous work published during the war, has been overlooked. It contains important ideas.

- M. Feldenkrais, Body and Mature Behaviour. London 1949 pp.127-9.

- P. Teilhard de Chardin. The Phenomenon of Man. Eng. Trs. 1959 pp.52-56, 71-74 and 84-89.

- The term was apparently introduced or at least popularized by R. M. Bucke in his book Cosmic Consciousness 1901. Bucke's own experience does not justify the term.

- Dramatic Universe Vol.II. pp.231-2 where it is described as the "motive force in the entire self-realization of all that exists". The Super-Ego is there called the Complete Individuality.

- The Individuality is treated as pure will whereas the self or selves are regarded as being associated with material existence. C.f. Dramatic Universe Vol.II, pp.129-32.

- Ibid. p.304-6.

- A Spiritual Psychology by J.G. Bennett to be published by Hodder and Stoughton, London, June, 1964.