ASPECTS OF THE SYSTEMATICS OF LANGUAGE II

The Domains of Discourse by S. C. R. Weightman

Systematics Vol. 7 December, 1969 No. 3

In a previous paper in this journal, an examination was made of the nature of 'discourse-experience' and a preliminary model was set up. This model represented the Universe of Discourse as a triangular pyramid, at whose apex was the Experiencing Self, for whom discourse was experience and unity, while, at the three corners of the base, were situated Language, Speech and Meaning. These three had been established as the primary elements of discourse in that they were universal, inseparable in any concrete experience, but such that it was not possible to reduce any one to the terms of either one or both of the other two. Standing at the three lower corners of the base of the pyramid they were represented, however, as if they were mutually exclusive components. The lines connecting each of these elements to the apex were taken to be the paths by which language, speech and meaning become experience. These paths were Competence, leading from language to unity, Performance, leading from speech to unity, and Grasp, leading from meaning to unity. Any point O within the pyramid represented a possible way in which the three elements can be fused in various kinds of situations. For a fuller treatment of this model and of the significance of each of these terms, together with a presentation of the generalised model developed in The Dramatic Universe* of which this is a particular application, the reader is referred to my previous paper, Aspects of the Systematics of Language**. For convenience of reference, however, the diagram is given here again.

*J. G. Bennett. The Dramatic Universe, Vol. I, 1956; Vol. II, 1961; Vol. Ill and Vol. IV, 1967.

**S. C. R. Weightman. Aspects of the Systematics of Language, Systematics, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1969.

The Experiencing Self

|

|

U - Unity L - Language S - Speech M - Meaning |

Fig. 1 Unity and Multiplicity

In the present paper, I shall attempt to penetrate more deeply into the nature of discourse, and to introduce further differentiations. This will be done by demolishing the preliminary model and then reconstituting it to allow room for 'other people' to inhabit this universe. It must not be thought that, because the experiencing self has been shown to be the unifying factor in discourse, and hence, in the initial presentation, was represented as the point of unity, the universe of discourse is solipsistic. Clearly the universe of discourse is rooted in society; but, with regard to discourse, the relationship between the individual and society is by no means obvious. There is a real problem here, and it is to this problem that the present paper is primarily addressed. It will be best to begin by turning our attention once again to the primary elements.

LANGUAGE

The first of the primary elements to be considered is Language, by which we understand the functional, knowable element in discourse which reveals itself in answer to the question, "What is going on?". In the earlier analysis it was decided that what was going on in discourse was utterance, and utterances were referred to as the 'process' of the universe of discourse. It is probably correct, even possibly inevitable, that this view of language should have been the point of departure, and that competence should then have been introduced as the path by which the raw materials of utterance become experience. There is, however, another viewpoint which stands, as it were, at the other end of the scale. This is the social view that regards language as the linguistic behaviour of a community, or, if one prefers, the behaviour of a linguistic community. Both of these aspects can be taken as answering the question, "What is going on in discourse?" Both are knowable and functional. We can hear, record and analyse utterances, and equally we can observe, describe and analyse the linguistic behaviour of a community. Thus language, in both of these aspects, is fully knowable. Language, in both of these aspects, is also purely functional, because, as we have said, functions are behaviour, that is the working of some mechanism. Utterances are the workings of the vocal mechanism, and indeed, utterances are often analysed on the basis of the manner of their production by the vocal organs. The view that treats language as behaviour, in doing so, regards the community as a vast linguistic mechanism, and language as the working of that mechanism. Thus when we speak of language as a primary element in discourse, it will henceforward be necessary to take account of both aspects, regarding the difference between them not as one of kind—for we have just shown that they are both knowable and functional—but rather one of emphasis.

SPEECH

The second primary element of discourse is Speech which, as we have seen, is connected with the action rather than the activity of discourse. In the previous paper it was said that speech has the power to organise discourse in depth so that discourse has the inner coherence whereby it becomes effective. "Speech has its differentiations in the power of expression and communication which vary from one utterance to another. There can be great differences in the expressive power of an utterance when it is used on different occasions."* This variation demonstrates the relativity of speech. "Speech is an intensive magnitude with the inner relation of 'more or less'. It can be represented as a scale on which the calibrations indicate the differing degrees of coherence and inner organisation. At the bottom of the scale would be 'undifferentiated speech sounds', at the top there would be fully cogent and effective speech, and there would be a series of gradations between representing the different transitions that have to be made to move from the bottom to the top. A single linguistic element like a word could travel right up and down this scale."**

*S. C. R. Weightman. Aspects of the Systematics of Language, Systematics, Vol. 6, No. 4, 1969. p. 303.

**ibid.

We cannot speak of speech in the same way that we speak of language. It cannot be said that speech is an attribute of a community in the collective sense in which we understood it when speaking of language, viewed in its social aspect, as the linguistic behaviour of a community. Speech is found in localised concentrations. Its arising depends upon finding a situation that matches its requirements. If two people speaking languages totally different in their phonological and grammatical structures were to attempt to converse, whilst they would probably be aware that the other's utterances were, for the speaker, fully competent and meaningful; the level of speech, that is to say the inner organisation and coherence of the situation, would not rise above the first graduation on our imaginary scale of speech, that is the level of undifferentiated speech sounds. If there were a closer relation between the two languages, then there might be a mutual appreciation of intonation patterns and certain structural features. In this case, the level of speech would move a little way up the scale. If, however, two people, with the same language and with similar backgrounds and outlook, were to converse, the situation would be such that there could be present a very great depth of coherence and inner organisation such as could lead to a sharing or a coalescence of experience between those taking part. There is absolutely no guarantee that it would result in this, for that would depend on the level of performance of the participants, but it certainly demonstrates that speech does require a situation that matches its requirements. When language was considered in its social aspect, it was seen as the collective behaviour of a linguistic community. Speech, however, is not social in the collective sense, but rather depends for its success on the matching and coalescence of individual speakers.

MEANING

The third primary element in discourse is Meaning. Meaning was defined as the principle of relatedness as a dynamic quality in discourse. Meaning was also referred to as the 'Why, How and Thus' of discourse. In the previous study we quoted the following passages: "In every situation there are both the particular thus and the universal why. Between these two, only the reconciling quality of how can provide a link, for 'how' is at once particular and universal."* This was illustrated by the example of a small boy and a park-keeper. The park-keeper's utterance presented its own unique thusness, and the small boy kept on asking 'why' at every level. Each 'why' was answered by a 'how' on the level above, until the final 'why' was reached, which was answered by the park-keeper's intention. To go beyond this, it was shown, would be to go beyond the universe of discourse. The term 'particular thusness' requires further clarification. Certainly every utterance has its own thusness, but, for this to be grasped, there is required an act of recognition or identification. It will, therefore, be more appropriate to refer to this aspect of meaning, not as 'thusness', but as identity.

*J. G. Bennett. The Dramatic Universe, Vol. II, p. 78.

Without entering into details here about the vast nexus of relationships that connect the particular thusness which we have called identity, with the ultimate why which we have called intention, it is possible to see that these two aspects of meaning could be regarded as standing to one another in the same relationship as utterance to linguistic behaviour and as undifferentiated speech sounds to fully cogent and effective speech. Of the two aspects of meaning, it is clearly intention that must be regarded as the 'social' aspect.

In the same way that linguistic behaviour was seen as the manifestation of a community in the collective sense, and fully cogent and effective speech as the manifestation of individual members of that community, so intentions, which stand, as it were, at the social end of the meaning axis, can be regarded as the manifestation of the needs and purposes of the community. Meaning is neither a collective possession like language, nor a reciprocal action like speech, but a state of affairs that is shared by those who can share it and can lead towards the shared experience that is understanding.

We have now made certain differentiations concerning each of the three primary elements of discourse which were not apparent in the first study. It is now necessary to reconstitute the model of the universe of discourse to take these differentiations into account.

THE DOMAINS OF DISCOURSE

In reconstituting the model to take into account the differentiations that have just been made, it is important to realise that nothing is really being added to it. It is rather being extended or drawn out into another shape that can more adequately represent the situation as it is now seen. In dealing with the primary elements, no mention was made of the fourth component of the original model, the Experiencing Self, whose role, in the universe of discourse, is always to act as the unifying factor. Indeed, because of this factor, discourse is truly a 'uni-verse' in that it 'tends towards unity'. Having made further differentiations, it becomes clear that the role of the experiencing self is the more crucial; because, not only does it serve to unify the three primary elements of discourse, but it has also to reconcile the two opposing views of each element that have just been discussed. The situation as it is now seen is represented by the diagram in Fig. 2.

|

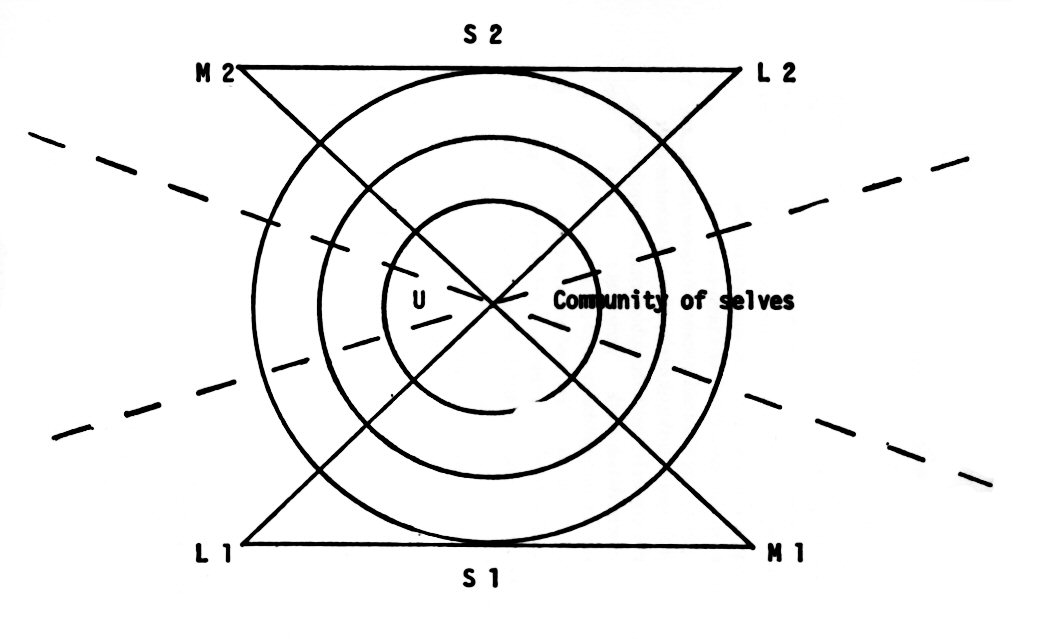

Fig. 2 The Domain of Discourse

In this diagram, discourse is represented as two triangular co-axial pyramids, in such a way that the apex of each pyramid lies at the point of unity. At this point in our researches, we can have no clear idea of which phenomena should rightly be assigned to which pyramid beyond the general criterion that the lower pyramid appears to be more concerned with the 'material' of discourse, that is to say with sounds and the structuring of sounds, while the upper pyramid appears to be more concerned with the social aspects of discourse. It would, at this juncture, be wholly inappropriate to attribute to these pyramids any of the dualities in current use in linguistics. Only at a later stage, when we have examined in detail the phenomenal content of these pyramids, will we be able to develop a suitable descriptive terminology.

What can be done now is to see the universe of discourse as comprising three domains. The first domain is represented by the lower pyramid, the second domain by the upper pyramid and the third domain by the point U. The point U represents the experiencing self, that is to say, the individual. From this we can say that the lower pyramid will represent the Subordinate Domain, that is to say that, within that domain, there is an ordering below the level of the individual. In the same way we can say that the upper pyramid will represent the Supra-ordinate Domain, that is to say that, within that domain there is an ordering above the level of the individual. Point U will then represent the Co-ordinate Domain, that is to say that, within that domain, there is a co-ordering of the other two domains.

The view that regards the universe of discourse as the supra-ordinate domain exclusively could be regarded as monism. The history of linguistics shows that this view is not without its adherents. Such an assumption is implicit in much of the work of the so called 'behavioural' linguists, and indeed in the notion of 'language-games' which arose from Wittgenstein's operational approach to meaning, which connected meaning with usage. On the other hand, the view that regards the universe of discourse as the subordinate domain exclusively, is pluralism. Here discourse is seen as atoms obeying laws. Such a view has been implicit in much work in linguistics until fairly recently. The third view that sees discourse as point U could be termed individualism.

The role of the experiencing self can now be understood more fully. The experiencing self unifies what is below in the subordinate domain and focuses what is above in the supra-ordinate domain. From the coordination of these two actions, it derives its experience. While a closer examination of the subordinate and supra-ordinate domains must await a fuller investigation of the contents of these domains, what is extremely necessary here is a much deeper understanding of what has been termed the co-ordinate domain. It is therefore to this that we shall devote the remainder of this paper.

THE DOMAIN OF REALISATION

The main weakness of this representation is that the experiencing self and the co-ordinate domain are shown as a single point. This certainly emphasises the unitive function of the experiencing self, and its position between the subordinate and the supra-ordinate domains indicates the co-ordinating function which suggested the designation of this domain. The single-point representation is, however, inadequate on several counts as we shall see a little later. While it is inappropriate at this juncture to use descriptive terms for the subordinate and supra-ordinate domains, it will perhaps be wise here, as a necessary corrective to these inadequacies of representation, to give the co-ordinate domain the strong name of The Domain of Realisation.* This word has been used in the linguistics in a weak, and, to some people's thinking, unsuitable way. For example it has been said that a word is 'realised' in phonic substance when it is spoken. Another school of linguists speak of a paradigm member being 'realised' when it is selected from the paradigm for use in a structure. In such contexts the word 'actualised' is probably to be preferred, reserving the word realisation for a process more in keeping with its meaning. From what we have seen, discourse is 'realised', by which we mean 'becomes real', only when it is experienced, or rather, when it becomes experience. Thus we mean by the domain of realisation, that domain of discourse in which, through the unification of the primary elements of language, speech and meaning, and through the co-ordination of the subordinate 'material' domain with the supra-ordinate 'social' domain, discourse becomes real to the individual who experiences it.

The first way in which the representation of the contact between the two pyramids as a single point is inadequate, is that it suggests that there can only be one experiencing self fulfilling the co-ordinating role at any one time, or else that there are as many universes as there are experiencing selves. Hitherto we have always spoken of the experiencing self in the singular. This was because the ostensible purpose of the first paper in this series was to examine the twofold role of the linguist as the investigator and the experiencer of his materials. This use of the singular, which the single-point representation appears to corroborate, can, however, no longer serve our purpose. It would be wholly incorrect to regard the universe of discourse as comprising a multitude of sub-universes, each individualised, and none having contact with the others. We have rather to see the single point as representing not a single self, but a community of experiencing selves.

It is necessary to distinguish between the Collectivity of selves that is society and the Community of selves that is the domain of realisation. It has already been shown that the supra-ordinate domain has its place in society, whether it is society seen en masse as the generator of particular patterns of linguistic behaviour, or as society seen as individual speakers who, when correctly matched, can provide a situation in which fully cogent and effective speech can arise, or as society, the sustainer of the state of affairs in which intentions can be understood. Society seen in these ways can be regarded as a collectivity of selves, membership of which depends upon a similarity of external roles. The domain of realisation, however, comprises a community of selves. That is to say, here selves experience unity together. The community is brought into being

when two or more individual selves make both the decision and the concessions necessary to share a common discourse experience. Membership of this community is determined by the inner criterion of sharing in a common decision and experience. Society, however, as we have said, is a collectivity of selves, united only by the external roles they are called upon to play. Every speaker belongs to this collectivity, but he can only belong to the community which is the domain of realisation, to the extent that he can share in a common experiencing of discourse.

This then is the first way in which the single point representation is inadequate. Through showing the domain of realisation as a single point it fails to indicate that this domain comprises a community of experiencing selves.

There is a second way in which the single-point representation is inadequate. Not only do selves merge in the domain of realisation; but each individual self carries with him a region of experience that has duration in time and extension in space. This region is the Present Moment of the self. In the act of communication, the present moment of two selves either partially overlap or merge into one and in this way extend the domain of realisation. The term communication has nowadays become debased but in the sense in which it is intended here it can be seen as the process that creates the community of experiencing selves that comprise the domain of realisation.

The present moment of a self is not fixed in its extent or duration, as can be easily verified from experience. Sometimes shrinking, sometimes expanding, in constant and perpetual flux, the present moment is, for us, as inconstant as the will of man that structures it. The possibility of the expansion of the present moment has considerable importance for the extension of the domain of realisation. In order to understand what is meant here it will be useful to consider an example taken from music.

Let us consider what can happen when one goes to a concert. It is first possible to sit, with one's eyes closed, allowing the music to fill one's experience, to move and evoke as it will. If one surrenders one's attention in this way, the music is one's experience and one's experience is the music. It is also possible, however, to listen more actively. This requires the expansion of the present moment in such a way that not only is the music still experience, but one is also able to 'take in' the structure and development of the work and the way it is unfolding. Such a widening of awareness also brings with it a heightened appreciation of the combinations of sounds, phrases and harmonies. With such a state of affairs we can say one is experiencing both the music and the work. A further widening of the present moment would come when, at the same time, one embraces the music, the work and the performance. When this happens one becomes aware of oneself in the concert hall with the rest of the audience, and of the orchestra and conductor playing the work in their own particular way. In this case the expansion of one's awareness to embrace, as it were, the whole auditorium also brings with it a heightened awareness of each note, with the particular quality, timing and emphasis that it is given on this occasion. Such, one imagines, is the embrace of music critics. Finally it is possible for a further expansion of the present moment which can bring the individual's present moment in contact with the greater present moment which is the universal experience of music in the life of man. Such a widening of the embrace of awareness, experiences the concert as part of the musical life of the community, it experiences the full potency of the coalescence of the composer, the orchestra, the conductor and the individual members of the audience, and sees the significance of this in the enrichment of the cultural life of the community. Such an awareness brings with it a heightened appreciation of the sounds in all the aspects we have mentioned, but also as musical sounds, that is to say having a different quality from other kinds of sound. At first sight it must seem that this last mode of experiencing music is the most primitive and attainable by anyone no matter whether he is tone deaf, totally ignorant of music, or standing in a noisy railway station. The difference is whether one is experiencing this from inside the 'universe of music' or merely looking in from outside. Only through such an expansion of the present moment as has been described, can the experiencing self be brought in contact with this region, from within, in which the special quality of musical sound, and the cultural role of music within the community, are together seen as aspects of the same universal experience.

The situation that has just been described is one that is, if not familiar, at least easily verifiable. Anyone who recognises what has been described, will also be familiar with the instability of the present moment. At one time it may be of sufficient extent and duration to embrace the whole auditorium and the particular performance that is being given, at another it may contract and be filled entirely with the experience of the music, being then of little more duration than a few bars. Such fluctuations are constantly occuring over very short periods of successive time.

A similar state of affairs prevails in the universe of discourse. Anyone who has been to a country where the language is unfamiliar to him, knows the experience of witnessing the universe of discourse from the outside. He hears sounds, which he knows to be speech but cannot differentiate, and he sees people behaving and communicating and obviously understanding one another, but he cannot enter the universe. A familiar stage in language learning is where the student is able to recognise and understand only words in isolation, but cannot yet structure them into sentences. Here he knows the frustration of grasping a word, but discovering that, by the time he has done that, the conversation is already several sentences on. When he can structure the individual words in the sentences in which they occur, he has extended the possible embrace of his present moment. Later in his studies, he will be able to extend it further so that he can embrace longer passages of speech and conversation. This refers to the possible embrace of the present moment. For a man speaking his mother tongue in his own community, where there are no limitations to the extent of the present moment of the kind that confront the language learner, there is still the question of the constant fluctuation. This we shall not pursue further here. It is sufficient to realise that the experiencing self is not adequately represented by the single point in Fig. 2, since the experiencing self is able, through the widening of his present moment, to come into contact with the regions in the universe of discourse which have been represented as the subordinate and supra-ordinate domains, and even to touch the most universal levels of these domains.

The musical analogy also shows one important aspect of the process of co-ordination that belongs to the domain of realisation. This is that, the more the present moment is able to expand and reach into the supra-ordinate domain, the more it is brought in contact with the corresponding region in the subordinate domain. The more the concert goer was able to embrace the occasion and the performance, the more aware he was of the particular quality of each note. Similarly in discourse, the more one is able to embrace a conversation, its situation and those taking part, the more one is also able to be aware of the exact manner in which each sound is articulated. It is because the present moment expands equally into both the subordinate and supra-ordinate domains, that there is able to be, in the domain of realisation, the co-ordering of which we have spoken.

The most serious way, however, in which the single-point representation is inadequate, is that it fails to indicate that it is only here, in the domain of realisation, that anything really happens. The starting point for the first study was that, for us, discourse is an area of experience. But it is clear that discourse is only one of many areas of experience, and discourse has no exclusive claim to our experience. The important point is that, only in the domain of realisation is there contact with the rest of our experience. Because this domain is open to the whole of our experience, it is only here that anything can happen.

But what is it that can happen? The expansion of the present moment of an individual self does not, of itself, extend the domain of realisation, but rather it establishes the possible limits of the domain at any given moment. It is the overlapping or the merging of the present moment of two or more selves that results from the decision to communicate which extends the domain of realisation. This is communication, by which we mean the sharing of a present moment. It is because at this point in the universe of discourse two or more selves can share the same present moment, and that here also the universe is open to the whole of our experience, that, in the domain of realisation, discourse not only can become real, it can also become Act. This is why we have continually insisted that the single-point representation does not begin to indicate the true significance of what takes place in this domain. In Fig. 3, we attempt to represent a little more adequately the domain of realisation by reducing Fig. 2 to two flat triangles, for convenience of representation, and showing the domain of realisation as a series of circles radiating from the point of unity. This shows the varying extents of the shared present moment which establishes the limits of this domain. The circles also show very clearly that extension in the upper domain brings with it an equal extension in the lower domain and vice versa. The dotted lines spreading out sideways from the point of unity are to represent that this domain is open to the whole of our experience. What also has to be remembered with regard to Fig. 3, is that grouped around point U is a community of selves in the sense which has been discussed above.

It is not solely because of the inadequacies of representation that we have devoted so much space to this domain. Much of what is to follow in these studies will be concerned with the subordinate and supra-ordinate domains, and to the elucidation of the phenomena which these domains contain. It is all too easy through being over-preoccupied with the complexity of these two domains, to neglect, and even to fail to take account of, the domain of realisation. To do this is to fall inevitably into polar thinking which proliferates dualities and leads to paradox and contradiction. Worse than this is that it produces a view of discourse that is unable to account for concrete situations, and thus is already out of touch with reality. To avoid this, it is necessary always to keep before us the coordinating and reconciling role that is performed by this domain, and to remember that only here can discourse become real and thus be enabled to play the vital part that it does in our lives.

Fig. 3 The Domain of Realization

SUMMARY

In this study we have differentiated the two extreme aspects of each of the primary elements of discourse, language, speech and meaning, and have reconstituted the model of the universe of discourse to take these differentiations into account. When this was done it was possible to see that the Universe of Discourse comprised three domains, which were termed the subordinate domain, the supra-ordinate domain and the coordinate domain. The subordinate domain appears to be concerned with the 'material' aspect of discourse and the supra-ordinate domain with the 'social' aspects of discourse. The co-ordinate domain was given the strong name of the Domain of Realisation, because it is only in this domain that discourse can become real. This domain was found to have great variations in extent because it depends upon the power of individual selves to structure and extend the embrace of their present moment and to merge their present moment into a shared present moment in acts of communication.

It is to be hoped that this investigation into the domains of discourse has prepared the way for the next in this series of studies which will be concerned with the framework of discourse, and will thus take us one step further in this examination of the implications of the ideas and insights developed in The Dramatic Universe for the theory of language.